‘In 18th-century Britain, landscape – even the picturesque landscape – was a mode of political discourse.’

Ann Bermingham, 2002

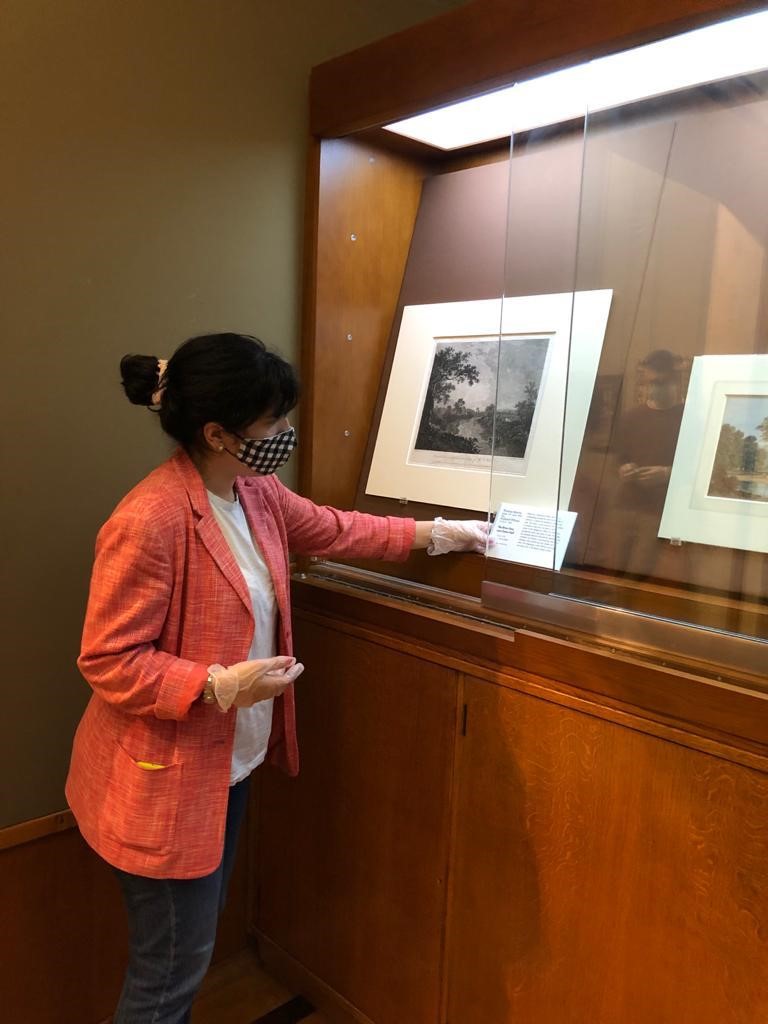

The Viewer and the Viewed features eleven works on paper from the Barber’s collection by artists such as Gainsborough, Turner and David Cox, and explores these breathtaking landscapes from a socio-political perspective.

Between the mid-eighteenth and the mid-nineteenth centuries, the British landscape was more than ever a subject of artistic production. This increased interest was both tied to the new importance of concepts like the picturesque within the British artistic and cultural discourse, and to more practical reasons like the French Revolution (1789-99) and the Napoleonic Wars (1803-15), which prevented English artists from travelling to continental Europe, and thus made them rely on their national landscape for inspiration.

These travel restrictions also favoured the development of domestic tourism among upper- and middle-class Britons. From the 18th century onward, picturesque tours were introduced, which allowed visitors to access a carefully selected array of locations within Britain, often private property that would, just on these occasions, open up to the public. An entire economy developed around the new phenomenon of national tourism, partially consisting of publication of tourist guidebooks, collections of prints depicting said picturesque views or the commissioning of smaller watercolours of the same subjects.

The development of tourism and of a market for cheaper and more accessible reproductions of picturesque views metaphorically overshadowed the upcoming political challenges to the privileges of the landowning class: up until then, accessing national landscape was mostly limited to them, together with political agency. It is key to keep in mind that land, at the time, had an especially strong political significance: only landowners had voting rights. Around the end of the eighteenth century, this electoral and political structure began to be challenged, encouraged by the revolutionary rhetoric coming from America and France. This culminated in the first Reform Act of 1832, which began the slow process of opening up suffrage to a broader share of the British population.

In the late-twentieth century, art historians began exploring how landscape art made in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries became a way for artists to take part in the political debate. This display explores how compositional elements of these works, like perspectival viewpoints and the figures inhabiting the scenes, can either reinforce or at times question who was given access to the land and consequently to political power.

The political significance of having access to land is particularly relevant during the COVID-19 pandemic, where current travel restrictions have not only made us appreciate our local landscape, but have underscored how access to it can still be a privilege. One of the most powerful aspects of art is that it allows us to reflect on our past while critically engaging with our present. Exploring these works from a political perspective reminds us how crucial it is to continue understanding landscape, and our environment, as a politically charged space.