Behold the man! Other ways of seeing Van Dyck’s painting

Celeste Garduño Carbajal

‘We cannot change the past, but we can change how we look at the past’ – Trisse Gejl, Steven Sampson (2020)

Behold the man! Other ways of seeing Van Dyck’s painting is a research project resulting from a 4-month internship undertaken by Celeste Garduño, thanks to the collaborative partnership between the MA in Curatorial Studies at the University of Navarra in Spain and the Barber Institute of Fine Arts.

The project aims

This project aims to unveil and question the representation of race in Van Dyck’s painting entitled Ecce Homo, at the Barber Institute, which was made in about 1625-26 during the artist’s trip to Genoa in Italy (1621-27). Why did Van Dyck decide to depict the soldier tormenting Christ just before his crucifixion as a person of colour, especially when two other versions of the painting (now at the Courtauld Gallery, and at the Princeton University Art Museum) appear to present a white Jewish soldier? What were the implications of this during the period in which the painting was made? And what are some of the implications of looking at this painting now?

This figure has barely been discussed in previous literature or exhibitions, despite there being only two figures in the composition – not to mention the striking, and problematic, way in which he is depicted and juxtaposed with Christ. The project attempts to interrogate and contextualise this derogatory and demonising presentation of a person of colour. This includes exploring the possible original patronage and functions of the painting, as well as discussing the racial violence and stereotyping that this work contributes to, and how this can be sensitively interpreted and presented to visitors today. By exploring these ideas and questions, the project hopes to contribute to an overdue reinterpretation of the painting, which includes a new gallery label and extended essay.

Celeste’s experience of the placement

Venturing into the complexities and depth of a single painting has been a challenge. Anthony Van Dyck’s painting Ecce Homo has forced me to put on my detective suit and remember that to be an Art Historian is to see beyond the canvas, always looking for new or previously hidden stories to tell, and that curatorial work is above all to situate oneself and to narrate. That is to say, to recognise your position and the place from where you are communicating, its limits and possibilities. To tell a story, or several stories, is not an easy task, but knowing the starting point from where you are telling it is an important part of the process.

Researching and reinterpreting an artwork with a ‘decolonial’ approach in part implies that there will never again be an authority, nor sovereignty over subjects, objects or questions, and even less so over answers. We must always be clear about the contexts and perspectives with which we approach an artwork and its interpretation, as well as recognising that it is our duty as curatorial professionals to help make visible what has long been invisible.

The painting: commission and context

The Ecce Homo painting was probably commissioned by the Balbi Family, devout Jesuits and powerful merchants and bankers, whose wealth came from the trade of all kinds of goods such as wood, silk, and spices, mostly with the Middle and Far East. Van Dyck arrived at Genoa having already made his name as a renowned artist and with good connections, which allowed him to quickly establish himself as the painter and official portraitist of families such as the Balbis.

Genoa was a deeply religious city, with great economic and political power. The city’s splendour developed during the 14th and 15th centuries, with its control of most of the Mediterranean seaports, its political relations with Spain and the so-called ‘discovery’ of America in 1492 by the Genoese Cristobal Columbus, allowing an unprecedented expansion of trade and cultural exchange.

A closer look at the painting

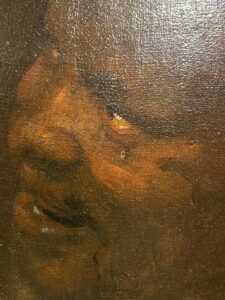

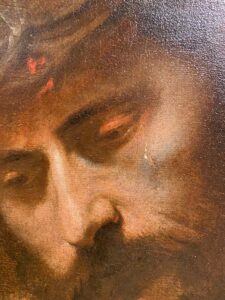

‘Behold the man!’ (Ecce Homo) are the words used by Pontius Pilate when he presented Jesus to a hostile crowd shortly before his Crucifixion. In this painting, Christ is mockingly being dressed up as King of the Jews by a Black soldier, with the crown of thorns on his head and a robe around his shoulders. The figure of Pontius Pilate has not been included in the composition, making it a more intimate meditative religious object. The work is not about the narrative per se, but about what the viewer sees, or even more, what the viewer does not see. The treatment of light and colour that highlights the whiteness and paleness of Christ’s body, in contrast with the obscure image of the Black soldier, as for the different emotions both figures portray, leads to a meditation on the ethical and moral connotations historically imposed upon notions of light and dark in a way that promotes piety, devotion to Christ and obedience to the Church. In this way, the painting upholds the relationship between whiteness and power, and reveals some of the parts that religion played in this during the 17th century.

This conveys an emotionally charged portrait of Christ with his tormentor, which confronts the viewer with a range of nuanced emotions and messages that at first can appear as hidden or as veiled as the Black soldier himself.

This painting was commissioned by the Balbi family, probably to help promote the Jesuit missions in the 1600s. Jesuits follow the teachings of St Ignatius, with a focus on education as one of the most important ways of promoting ‘the betterment of souls’. Indeed, when Van Dyck was painting Ecce Homo in Genoa, the Balbi family, following in the footsteps of St Ignatius, were undergoing a lengthy process of founding a local Jesuit college, now the site of the University of Genoa. This focus on education extended to a profound interest in conversion. Conversion was a focus for anyone considered to be non-Christian or un-Christian, including rural villagers, women, and North African people, often Muslims. Further afield, the enslaved Africans in the Americas were the focus of Jesuit missionaries. Was the decision to show Christ’s un-Christian, evil tormentor as a Black soldier made to demonstrate the Jesuit mission to convert these groups of people? As such, Ecce Homo is an artefact of racial demonisation and exemplifies the interconnected nature of race and religion in Early Modern Europe.

When making the contrasts between both figures in Ecce Homo so evident, as with Van Dyck’s specific use of light and colour, which reduces the Black solider to such a problematic moralistic representation, one may ask what are we truly meditating on when viewing this painting?

‘We cannot change the past, but we can change how we look at the past’. By looking at this painting from different points of view, we are not only changing the way we look at the past, but we are also questioning its narratives. And thus, ‘unlearning’ who it is we should really be looking at next time someone says: ‘Behold the man!’

Thanks to Becca Randle, former Learning & Engagement Coordinator, for her original research and contributions to this project.