A revelatory project undertaken by the Barber and the University’s College of Medical and Dental Sciences has explored the fascinating part played by women in the hidden history of a common wild plant – and its role in the treatment of heart disease.

Reclaiming the Foxglove is the first instalment of an ongoing partnership between the Barber’s Learning and Engagement team and the College. The gallery’s Student Engagement Co-ordinator, Kirsty Clarke, explained thatch team had been approached about a creative collaboration by MDS’s Diversity Inclusion Group.

“They were thinking about the environment of the medical school and how they could make MDS a more welcoming and inclusive environment,” said Kirsty.

One of the proposals was prompted by a consideration of the portraits around the college of important people who had contributed to the medical school – and medicine generally.

“There was a real lack of diversity and representation among them: they’re all older white men – particularly in the older building,” said Kirsty. “The Diversity Inclusion Group wanted us to hold creative workshops, potentially with practising artists, to encourage students and staff members to reflect on the histories of the Medical and Dental School – and medicine in general – and think about the contributions of women and people of colour that are often sidelined, ignored or erased from history.”

The story of the ‘discovery’ that botanically sourced digitalis could be used in the treatment of the heart-disease related condition dropsy was a typical example. Physician William Withering (1741–1799), one of the co-founders of Birmingham General Hospital, is widely celebrated for his research into the medicinal properties of digitalis, originally obtained from the leaves of this common wild flower. His 1785 publication An Account of the Foxglove and Some of Its Medicinal Usesdescribed digitalis preparations and their efficacy in minimal doses in the treatment of dropsy. A portrait of Withering, with a sprig of foxglove resting on his lap, hangs near the entrance to the medical school.

“Withering is credited with finding the correct dosage of digitalis, and is connected with the early days of Birmingham’s medical school, when it was in the city centre,” said Kirsty. “There’s an account in one of his books about digitalis, where he makes reference to an old woman in Shropshire. He writes that he obtained this recipe from her family – it included about 20 different herbs and flowers, and it was administered to people who suffered from dropsy. He was asked to investigate this and deduced it was the digitalis in the tea that was effective in treating dropsy. He did a series of tests on different patients to find the correct dosage – because if you take too much digitalis, it is lethal.

“What was interesting was the references to ‘wives’ or ‘old’ women – they’re all unnamed, so it made me think about women’s contributions to botany and herbalism. In the 18th century, doctors were expensive, and working-class or poor people in rural villages didn’t have access to them, so they would turn to woman in the community, who would give them different herbal potions and elixirs. I thought it was interesting that these recipes were taken from these women – and to question who gets to write the narratives.”

In fact, Withering’s mystery ‘old woman’ had been given an invented name, back in the 1920s, when pharmaceutical giant Pfizer created an advertising campaign for a digitalis-based drug featuring an old woman they called ‘Mother Hutton’.

Kirsty led Zoom sessions for staff and students over the late spring and summer that delved into this history, including an online workshop with botanist and broadcaster Alys Fowler, who delivered a potted history of herbalism looking at the role of women in medicine and history, as well as identifying plants on campus with medicinal properties. Birmingham-based writer Adrian B. Earle led a creative writing workshop that explored ideas such as botanical discoveries in colonial histories, and reimagined the story of the Shropshire woman, writing short, speculative fiction narratives. Poet Jasmine Gardosi led a creative-writing session where participants created potion and tincture recipe-poems responding to plants foraged around the University such as dandelions, chickweed, sticky-weed – while others wrote from the imagined perspective of a plant.

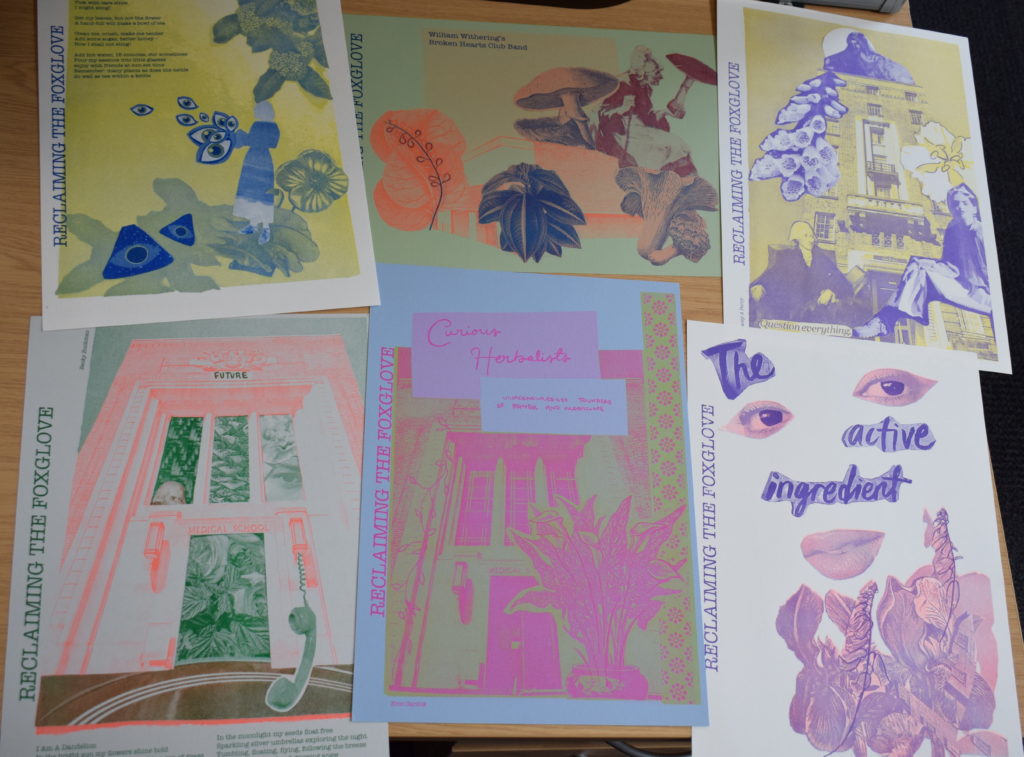

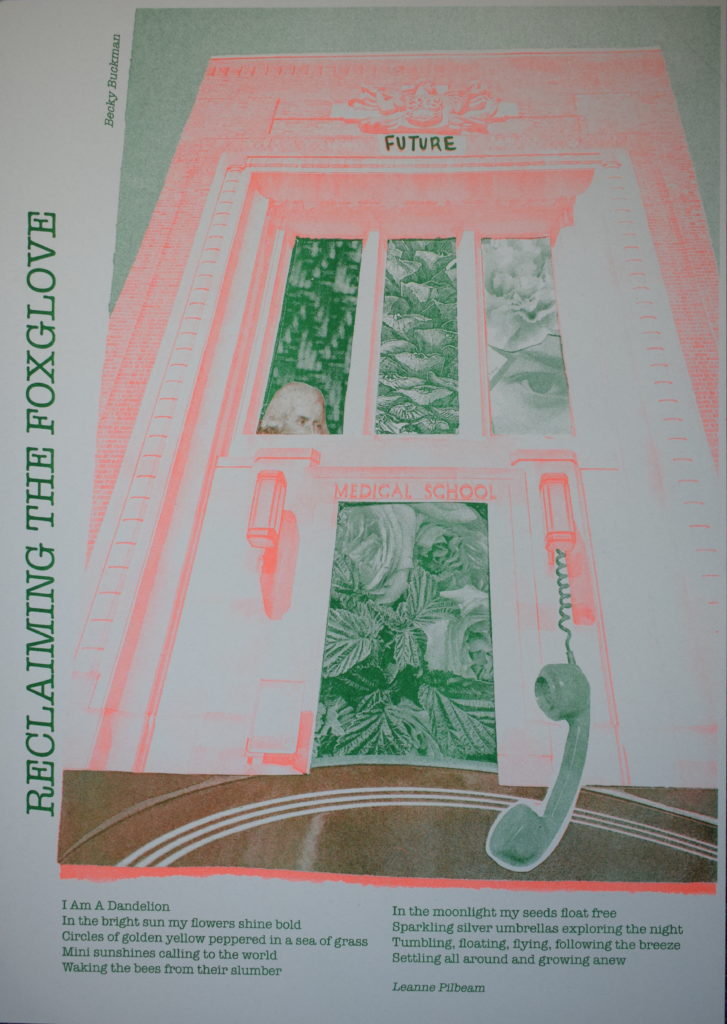

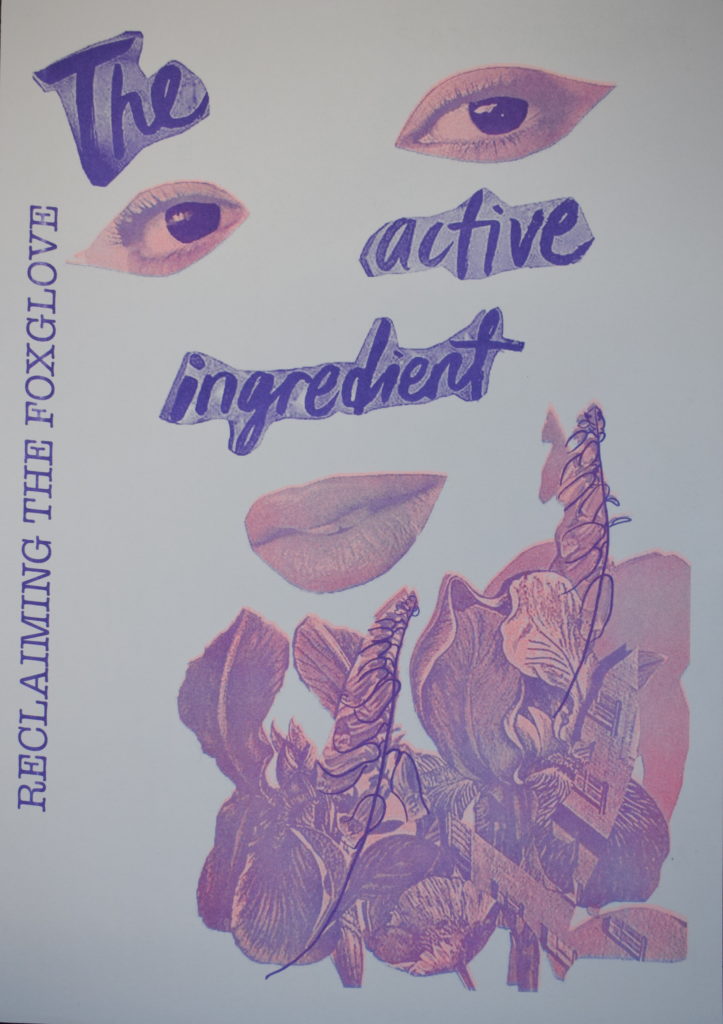

The final workshop, led by Kirsty, involved creating digital collages, which were then combined to make posters – printed in plant-based ink.

“They look a bit like Monty Python illustrations,” said Kirsty. “They included images I’d taken around the medical school, pictures of William Withering, and ‘Mother Hutton’, botanical drawings – it was our way of reclaiming these narratives around the medical school.”

It is hoped the posters be displayed soon in the medical school building, said Kirsty. “I hope they spring up in unexpected places – a bit like weeds – peppering them around the school and making a display of them as near as we can to the William Withering portrait.

“It’s not to say that William Withering was a bad person, but so much of this history is hidden,” adds Kirsty. “It’s about uncovering and celebrating the contributions of all these people, and we don’t know about them without doing the research. It’s a question of who gets to write these histories – and whether we can reclaim them.”