Hellenistic Coins

The Barber Institute collection of Hellenistic coins is small but contains some fine specimens of early Greek coins, the earliest examples of ancient western coinage. It also contains some of the most beautiful and finely struck examples of Greek royal coinage. The reign of Alexander the Great provides a valuable case study of the powerful symbolism and metallic fineness of Hellenistic coins.

A splendid gold stater struck in the name of Philip II of Macedon was acquired in 2002. On Philip’s stater the God Apollo, considered the legendary ancestor of the royal house of Macedon, is pictured as a splendid and healthy youth, strongly resembling Philip’s son and heir, Alexander. Alexander’s own coins in the Barber Collection range from a gold stater to tiny silver obols. Powerful images of female and male deities adorn the coins along with the royal portrait, associating Alexander with images of wisdom, victory and royal power.

Alexander was to succeed his father and lead a war of conquest across modern Greece and as far as the borders of modern India. His silver obols echo the new resources and of the area conquered during his reign. His army’s expedition across Egypt and the former Persian Empire as far as Bactria (modern Afghanistan) brought him the hoarded treasures of Pharaohs and the Achaemenids of ancient Mesopotamia. Coinage was now introduced on an enormous scale, with mints opened in Asia Minor, the Levant, Egypt and at Babylon, producing gold, silver and bronze coins. Alexander’s conquests in the late 4th century BC created a vast and unique empire, where different cultures were blended with a Greek-language administration to create a vast and diverse empire. Following Alexander’s death in 323 BC his former generals began to compete for shares of his empire, which for a brief period had been one of the largest unified political structures in recorded history.

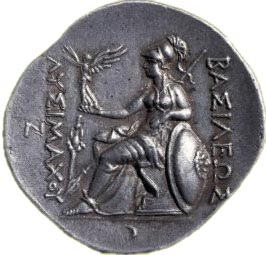

The coinage of Alexander’s successors conveys the political ideology they sought to convey to their subjects, centred on the Greek language and their claim to be the rightful successors of Alexander. Designs are of the highest quality and often very realistic. The portrait of Alexander, introduced on coins of Ptolemy I, Lysimachus and Seleucus, was kept on many of these coins representing their public loyalty to the memory of Alexander. The Barber possesses a beautiful silver tetradrachm of Lysimachus struck after 281 BC, commemorating Alexander’s legend and his importance to the new king. During his visit to the oracle of the Egyptian deity, Zeus Ammon, in Siwah (Egypt, 331 BC), Alexander had received divine honours for the first time, and the obverse design of the tetradrachm is an impressive portrait of him, wearing the ram’s horn of Ammon, underlining his divinity. By extension, this coin suggests, Alexander’s successors too could claim divine authority.

These later coins, struck after Alexander’s death but still carrying his portrait, show Alexander’s gradual transition from historical reality to culture-hero. He was later commemorated in Arabic literature as Iskandar Dhuílquarnein (two-horned Alexander), and found his place among the prophets in Sura 18 of the Quran. Many medieval and renaissance rulers claimed legitimacy by asserting that they were valiant successors of the young king, who left at his death an empire stretching from the Straits of Gibraltar to the Indus River.

The Master of the Griselda Legend (Italian artist, active c.1500) offers a glimpse of this 16th-century ideal in his painting Alexander the Great, which once adorned a Siennese palace and is now in the Barber Institute. The youthful soldier Alexander stands above an inscription, which served as a constant reminder to the important Piccolomini family for whom the picture was made of the virtues of an ideal ruler:

‘I Alexander, who conquered the whole world with my own strength, shook off the flames of desire from my heart. It is of no avail to rejoice in the outward triumphs of war if the mind lies sick and rages within’.